My conversation with Mr Andreas Junghanns

Published: March 1, 2025

In March 2024, I became interested in the history of Sokoban automated solvers, particularly Rolling Stone, which was frequently mentioned in research papers but I didn’t find any picture or binary that would allow me to easily get an idea of what it was like. Since the published source code was for Unix and dated back to 1999, I wanted to make it accessible to modern users. This led me to adapt it specifically for Windows.

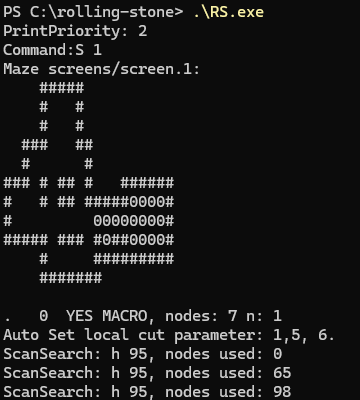

Here is a screenshot of Rolling Stone:

By February 2025, I had solved 53 puzzles from the XSokoban set. However, I discovered that the latest version, mentioned in a 2001 research paper—whose source code was never released—could solve 59 puzzles. This prompted me to contact the main author, Mr. Andreas Junghanns, to ask about this version, which introduced the "Rapid Random Restart" feature. He responded, and we began an engaging conversation. I had more questions in mind, hoping to uncover answers that would interest Sokoban fans.

Important note: Carlos Montiers Aguilera’s messages start with a >

> Hi Andreas,

Hola Carlos - muy bien conocerte!

I don’t want to torture you with the rest of the Spanish that I still have after so many years hardly using it... :(

> Your paper and the Rolling Stone solver have been incredibly important in Sokoban AI research.

> A Question About the 59 Levels:

> In your 2001 paper, "Sokoban: Enhancing General Single-Agent Search Methods Using Domain Knowledge":

> On pages 225 and 226 (PDF pages 7 and 8), the table shows 57 solved levels, including "R10 = R9 + Rapid Restart."

> On page 237, it states: "For each of the unsolved problems, an additional search to 200 million nodes was performed. This resulted in two more problems being solved (numbers 25 and 28), bringing the total number of solved problems to 59."

> However, in the previous table, level 25 was already included, but not level 28. Wouldn’t that bring the total to 58 instead of 59?

> Additionally, there’s another mystery:

> The status page (https://webdocs.cs.ualberta.ca/~games/Sokoban/status.html) from 1998 lists puzzles 46 and 47 as solved, yet the 2001 paper does not.

About the levels solved: This is confusing at first, but the explanations are simple: a) I might have made a mistake - this is not very likely because Jonathan was watching very attentively what I did and how the numbers increased, but still possible b) when adding a new heuristic, we sometimes lost a problem or two that we could previously solve - there was no natural progression in success. It was a rather tough way of trial and error about what worked and what not.

> I’d also love to feature a mini-interview with you on my site, Sokoboxes.com.

> It would be great to include more discussions with key figures in Sokoban history. If you’re open to it, I’d love to ask a few questions via email

> Of course, feel free to answer as many or as few as you’d like. Any thoughts you can share would be greatly appreciated!

> Looking forward to hearing from you. Thanks again for your time!

Mini interview: a pleasure to answer your questions to the best of my memory :)

> How did you become interested in Sokoban?

Someone in the GAMES research group at the Computing Science Department of the University of Alberta (Edmonton) pointed the group to XSokoban. Teasers, puzzles (physical) brought bags from trips, especially Japan, games of skill, like the levitron, were a constant joy among the grad students, professors and visiting professors. We held games parties in Edmonton and puzzles, games, game ideas (like a self-build 3D chess), (lots of food) and heated discussions created an incredibly stimulating environment.

> When did you first play Sokoban?

We all tried XSokoban.

> What motivated you to create a solver?

I was and still am very annoyed and impatient with my own limited intellect. I lost in chess against my girlfriend routinely (she was a club player in East Germany from the age of 4 or 5) and I started building chess programs to enhance my mental ability and hoped I could win against her that way: my first program was Chessitz (really bad and slow) and later with Yngvi Björnsson TheTurk. For my PhD work, I had tried a number of ideas on how to improve TheTurk which all failed.

I was thinking about what to do next (when the chess ideas failed) and solving Sokoban seemed like a good distraction (how hard could it be?!) until some new idea on how to improve alpha-beta search for chess might emerge. You can imagine our surprise and dismay when all our text-book single-agent search methods failed to solve even the simplest of the beautiful 90 problems in my first text-book (naive?) attempt. It was a challenge that we discussed in the GAMES group. I got sucked into Sokoban: The simplicity of the rules, the beauty of the game, the emerging complexity... throwing a machine at the challenge seemed the most natural thing to do at the time. We - the members of the GAMES research group - had solved many, many other puzzles after a few days, some after a few weeks - we expected no less here.

> When you started creating Rolling Stone, were you aware of any good Sokoban solver?

Not at first. Remember: this was 1995, maybe 1996; the internet was new, search engines did not exist yet, and I was not a patient searcher through newsgroups. I visited Japan in 1997 for IJCAI-97, where I presented a paper (Sokoban: A Challenging Single-Agent Search Problem). Some friendly Japanese researchers approached me shortly after and mentioned a solver that could solve many more problems than I had reported at the conference. It turned out to be the "Sokoban Laboratory". Its approach differed from mine; while I focused on optimal solutions, it produced non-optimal solutions, but for more problems. I found it interesting, but I continued with my own ideas.

> Looking back, is there anything you wish you had done differently with Rolling Stone?

Oh, yes! I would be way more methodical today in how to develop the code: git, diffs, continuous integration and regression testing on small and selected bigger problem sets... we could have pushed the limits without focusing so much on the huge search-node numbers and measure success with that thereby speeding up the feedback loop.

But we loved to see the big numbers and that distracted me quite a bit. Also: maybe we should have given up earlier on the optimal solution quest: Any solution is better than none. I am still not sure how that would have led to original research though.

Also: I started working on a general search program: a rule description language for state changes and then a program that would try to solve problems there (start states and end states). I worked for weeks and tried to generalize ideas from RS. I ran out of time in 1999. Maybe I should have started earlier to move from one specific domain to a more general problem solver?

> Do you have any plans to develop new solvers in the future?

I am focusing on other hard problems these days. If you care, have a look at explai.com - we are trying to use AI methods to solve hard, real-world problems.

> Are you still researching Sokoban or working on similar AI problems?

Unfortunately no. I wanted, for a long time, to go back and clean up my code: I am convinced there are bugs in there that today we can find more easily using modern versions of lint, like Coverity, or run-time checkers. Actually trying to improve the AI of the code might have come later, the more pressing urge was to clean up. And no, no similar problems. The last time I developed a solver for a game I got into trouble because I spent 4 days writing a solver for a silly game my kids got for Christmas and nobody around me shared my joy of producing optimal answers to a stochastic game using some "clever retrograde analysis"... I miss the days of the GAMES research group when problems and solutions like those seemed the most important in the world for all the people around you :)

> Why was the last version of Rolling Stone never published?

In 1999 I went back to Europe, started working on engineering problems, like automated failure mode and effect analysis, AI-driven test methods of complex technical systems simulated as high-fidelity digital twins (hardware and software co-simulation), standardizing simulation interfaces (fmi-standard.org). I changed tack completely, got sucked into that 100%, eventually with our own company etc. And Rapid-Random-Restart never felt like a true AI method. I thought that this was a hint that we should approach search differently - I just did not figure out how to do that in the remaining weeks I had in Canada before starting my job in industry research in Europe. And Monte-Carlo Search, just a few years later, did something quite similar so much better.

After a bit of digging, I found my research log and the code with rapid random restart (RRR): I sent it to you, feel free to publish that version as well.

[Carlos’s note 2025-03-24] That was an early RRR version, not the final one. Some puzzles solved in the final version couldn’t be solved with this one. Despite Andreas’s efforts to track it down—carefully searching through old files and folders—the final RRR version hasn’t been found yet.

I hope that answers your questions - if not, feel free to keep asking!

> From the XSokoban puzzle set, do you have any favorite puzzles?

No - there are so many different aspects exemplified in the different puzzles, I cannot choose.

I found the kids’ problems often much better: smaller and in some sense often harder or surprisingly hard - beautiful embodiments of the wonderfully complex Sokoban world created from very few, simple rules.

> How popular was XSokoban when you played Sokoban for the first time? Did you play other versions, for example, the official Soko-ban for DOS?

We used Unix only at the time, even my PC ran Linux: I only knew XSokoban and I was quickly tired of playing the game itself.

As said before: I rather code.

> Did you ever take a look at other solvers like JSoko or YASS?

I did not know about many solvers at the time. We wanted to push AI methods AND solve Sokoban problems. Code of others without a scientific paper was of little value to us, besides curiosity.

> Have you considered releasing a remastered version of Rolling Stone?

Yes, running static code analysis to find bugs, instrumenting the code to find run-time bugs... but it would remain a command-line tool. Sorry.

> What was Jonathan’s contribution to the research, or who was responsible for each idea? How did you work together?

Jonathan was always there to bounce ideas off - his quick and critical

mind challenged any idea I had and we refined it often at the black

board. During GAMES research group meetings, we did the same: someone

presented a new idea and then the group hacked away at it.

So I am sure most of the ideas are originally mine (while I had the

privilege to focus 100% on Sokoban, Jonathan supervised many research

projects back then), but I benefited tremendously from discussion and

input from Jonathan Schaeffer, Yngvi Björnsson, Darse Billings, Aske

Plaat, Roel van der Goot, Tony Marsland, and last but not least Neil Burch (sorry if I forgot others).

> Regarding Rolling Stone:

> Which ideas were completely new?

> Which ideas were already known but improved?

> Which ideas were simply adapted for use in the solver?

My thesis makes that clear: there are "standard" methods - known from text books beforehand. And then the new ideas.

Thesis writing requires delineating where related work exists, where previous work was used and what ideas are original.

Please check that in the thesis - especially the related work.

> Additionally:

> Do you have any new ideas or algorithms that you think are promising? (Ones that aren’t widely known yet—perhaps ideas that emerged after your papers were published.)

We had a saying back then: Ideas are cheap, making them work is hard. I think my thesis has a chapter with ideas we tried and that did not work. So it would be far from me to judge an idea as promising without actually trying it as success and failure are maybe just weeks or months of hard work apart.

> Do you think humans will always be superior at solving Sokoban, or will machines eventually surpass human players?

During the last 25 years I would have answered this question differently, at least 3 times. In 1999, I would have believed only humans will excel at the hardest Sokoban problems forever. A few years later we saw the amazing progress made at Go and it seemed a door was opened to new ways of approaching hard problems using advanced AI methods. Today, I believe that humans will eventually also have to concede Sokoban-supremacy to machines. However, humans will remain for a long time the only intelligence to actually enjoy the beauty and intricacies of Sokoban. Like in chess: even the best humans get crushed by the machines, but we still have fun playing the game. No algorithm can take THAT joy from us, if we do not allow it.

> What do you think was the biggest breakthrough in Sokoban AI since your solver?

I don’t know. I am told that there is at least one program now that can solve all 90 "standard" Sokoban problems - how they do it, I have not kept up with and I am quite sorry not to have spent the time to stay current on that.

> Since Sokoban is one of the few games where humans are still much better, why doesn’t it get more attention in the research community?

I have no idea, really. I am not sure what the current state of the art is - so it is hard for me to judge what the next steps could be for research. Maybe LLMs for planning? See below.

> Since you mentioned, "we are trying to use AI methods to solve hard, real-world problems" do you think modern large language models or deep learning could be used to develop a new best solver? What impact may these advancements in AI have on the Sokoban domain?

I think the challenge will be to combine the "intuition" of the LLMs with the precision of a Sokoban backend. When we tried planning methods in the 90s to solve Sokoban, planning was very limited and not very creative. This could be the part of the LLMs now - but it needs the rigor of a backend that pushes back on impossible ideas/solutions/plans. How to code that I only begin to understand now (early 2025) but - as mentioned above - I am involved with explai.com, that is where I spend the time now.

Solving more problems is likely not that interesting to humans. I would rather like to work on creating new problems: especially finding small, almost impossible problems that are hard for humans - would that not be fun?

—